Top Bar (Swarm) Bait Hives: Getting Free Bees

Yearly Updates – Catching Swarms with Bait hives

I continue putting out my bait hives and catching 12 – 15 swarms each spring, except for 2020 due to the pandemic. For the spring of 2022, I have found 3 new sites where I caught swarms in 2021. I plan to put more bait hives in those locations. The scouts bees were fighting each other at those locations (in 2021). Scout bees fighting at a bait hive indicates that more than one swarm wanted that bait hive. So I put 2 or 3 bait hives there, if not that swarm season, then the next swarm season. If you see scout bees at your bait hives, watch them from down wind and do not disturb them.

Note: In Spring 2016, I caught, ironically, the same number of swarms as in 2015, 17 swarms or again about 30% of my bait hives caught swarms.

However, we had a cool rainy weather right in our main nectar flow. The early Spring swarms were large before the bad weather. After the poor weather subsided, the swarms were small. So the numbers do not tell everything. Size matters with swarms. In the summer, I had to unite most of the small swarms, or strengthen them with brood from other colonies, according to good bee management. In all, 2016 was not as favorable for catching swarms, but that is beekeeping.

Note: In Spring 2015, I caught 17 swarms or 30% of my bait hives caught swarms. This was a typical swarm-catching season for me.

Catching Swarming in Bait Hives: Introduction

Bees have become expensive and valuable. A three-pound bee package can cost up to $100 with shipping. I figure the loss of a prime swarm is like a $100 bill flying out of my bee yard–not acceptable.

Bait hives are a clever and a bee-smart way to catch swarms. Anticipating Spring 2012, I put out 19 bait hives (down from my usual number of 40-50 bait hives because I was getting my book on top-bar hive beekeeping to press). Nevertheless as photographed below, I caught plenty of strong swarms, 12 in all (63% bait hive occupancy), or about $1000 worth of recovered bees and swarms from feral sources. I have been catching swarms like this for decades. Here are some swarms coming to my bait hives just from Spring 2012.

Swarm Clouds Entering Bait Hives

In Spring 2012 we witnessed, remarkably, four swarms entering my bait hives. A big swarm cloud coming to a bait hive is one of my favorite scenes. I enjoy being in the swarm cloud, feeling its hum, and seeing the mesmerizing effect of all the bees swirling around, their wings glittering in the sunlight.

Below, this big swarm came from across a large field to my bait hive. I heard them coming. The swarm was not from my apiary since I had just finished inspecting my hives.

During the spring rush, there is little time to work on top-bar hives at my bench under the shed. Since no kids or pets are around, I just leave a bait hive right on the work bench and another on the sawhorses, making use of this sheltered place.

The morning sun warms the hives allowing the scout bees time early in the day to start their inspections. In the afternoon, the shed roof keeps the bait hives from getting too hot and provides a wind shelter. I also store hive equipment under another open side of this building. That equipment releases more hive odor to attract scout bees. With my research apiaries nearby, swarming is hard to avoid. My standard practice is to surround these apiaries with bait hives like the work bench site, making creative use of the available buildings. First a swarm came to the bait hive on the bench. I am searching through the bees around the hive in case the queen is not in the hive. As explained in my book, swarm catching is queen catching. The bees will not stay in the hive without the queen. Since I am here when the swarm is moving in, I want to make sure the queen does not get lost on the outside of the hive.

The next swarm came to the bait hive on the sawhorses.

At another small shed near the one with the work bench, I made a roof off one side to shelter a pile of used top bars. On the pile of top bars, which smells like propolis, with a beehive smell to attract scout bees, I put a bait hive. The hive is not high off the ground, but the little roof makes a nice sheltered location along with a hive furnished with some comb. With all the propolis odor, the scouts found the hive quickly, and they inspected it for about a week. Then a swarm descended on the hive as Suzanne and I arrived home from work one day.

Bait Hives and the Modern Apiary

In my opinion, bait hives should be a part of a modern up-to-date apiary during swarm season. In particular, suburban and urban beekeepers should use bait hives near their apiaries to help keep their swarms from causing problems. That is why I included a detailed section on bait hives in my top-bar hive beekeeping book because I felt the book would have had a bad omission without it. On this page I give additional pictures and information about bait hives specifically for top-bar hives that enhance the bait hive section in the book.

Before getting to the bait hive details, here is my standard warning: For beekeepers located in or near regions with Africanized Honey Bees (AHB), including seaports where swarms could arrive on ships, be cautious about using bait hives because you could get an AHB swarm. Contact your state personnel with apicultural duties to see if bait hives would be appropriate or what extra measures would be needed, such as immediately requeening the swarm with a queen from a known stock.

Catching Swarms Near Your Apiaries

Even after applying swarm prevention and control practices (as explained in the Management Chapter of my book), some colonies will swarm, a fact of beekeeping life. Then in the spring, bees sometimes go crazy with swarming from poorly understood environmental conditions. That seems to overpower most of the good management practices meant to thwart swarming. Instead of feeling outmatched when I see a mega-swarm bending down a big branch way up in a tall tree, far too high to climb (and I do climb if at all possible), I want a possible ace up my sleeve to lure those wayward bees back home again. And that ace, actually a deck of them, is my small “army” of bait hives. On the other hand, sometime swarms come out of the woods and go into my bait hives placed near my apiaries. How do I know? Because I watched them as photographed above. In addition, I have another critically important use for bait hives.

Hunting Survivor Stock with Bait Hives

In addition, I catch swarms in bait hives from feral colonies with stock apparently surviving with varroa mites. Those bait hives go into areas with known feral bee populations, but away from managed apiaries. Typically my bait hive occupancy is low in these bait hives, a high risk of failure – but that is not the point. I know I will not get a lot of swarms. Rather, I hope to get one or two swarms (likely nothing), kind of “rare” survivor stock swarms from deep in the woods or from secluded swampy areas. Here is an example. At a rural county dumpster the operator knows I am the “bee man.” He tells me about a few bees coming to the water hose (by the dumpster) during a dry summer dearth. No beekeepers or houses are in that area. I show him how to get a bee-flight bearing from a water location, to get the direction to the hive, when the bees appear at the hose again. Later on, the direction he shows me is straight into a swamp with fairly big trees (that could have hollows). Also bees do not fly far for water so the colony should be fairly close. That is a good area for bait hives and hunting possible survivor stock. Part of the lesson here is that looking for bait hive locations for survivor stock is a year-round activity. I am learning about this location in the summer; the bait hives go out there during the next spring (see the Timing section below).

If that caught bee stock (swarm) evaluates well with additional testing (for gentleness, honey production, etc.), I graft queens from that survivor queen and use them in my other colonies. Finding survivor queens with bait hives is one way I keep my miticide (“chemicals”) use at zero. Understand that the old mother queen of the prime swarm of the surviving stock carries the desirable genes – exactly what you want. Even the after swarms, which have the mother queen’s daughter queens, are still good candidates for survivor stock.

Bait Hive Planning

For getting some 50 bait hives ready, I plan the equipment usage in the previous fall and winter. That means mostly having enough hive bodies, top bars with foundation strips for new comb construction, and empty brood combs. Below I am installing about 600 foundation strips, many of which will go in my bait hives and for other new colonies. By the way, Foundation Strips are the Gold Standard for getting straight combs. And when my bees are building hundreds of combs in a season, I just cannot have a third of the combs come out crooked or wavy or lopsided as can happen with wooden comb guides. (I have gotten dozens of emails from beekeepers complaining about crooked combs with wooden comb guides.) I must have virtually ALL my combs straight and interchangeable among any hives. These foundation strips provide such straight combs. Furthermore, I have used this method since the 1980’s.

Equipment for My Bait Hive

A bait hive is an empty hive made attractive to the swarm’s scout bees that choose the nest site. I use two-foot long hives, which came from my pollination operation. That hive volume is large enough to catch swarms while not being too long to handle for placing the hive on an extra tall site (see below). Occasionally I have used three-foot hives, but they are more awkward to handle overhead. (I do not think all that volume is needed. One could use a following board to partition off about the last one foot of the hive. I do not routinely use following boards, mainly because it is just more equipment.)

To make the bait hive attractive, I use an older hive body well propolized on the inside (for the odor). Of utmost importance though, I put two or three old empty dark brood combs in the hive. These combs are powerful attractors to get the swarm to take the hive. To work properly, these combs must be empty: no pollen containing cells, which could support wax moth larval infestation. And no old leftover granulated honey in the cells, which could attract ants and might cause the scout bees to reject the hive.

In between the combs, I put top bars with foundation strips. Upon the swarm’s arrival, the bees are ready to build comb – so let them by providing space between the combs. Even if I have plenty of comb, I do not “fill” the bait hive full of comb because in a sense it “wastes” the fast comb construction ability of a new swarm. The plywood at the back of the hive just helps limit the number of top bars per bait hive since many of them will not catch swarms. Warning. A big swarm can fill the front end of the bait hive quickly. Then the bees start building comb from the plywood, filling it with honey, pollen, and brood. All wasted effort because combs must be built from top bars for individual comb inspection. Even if the hive cannot be removed, at least look inside from the back to see how close the cluster is to the plywood. If close, replace the plywood with top bars having foundation strips. If the plywood feels “heavy,” even before peeking underneath – you’re late!

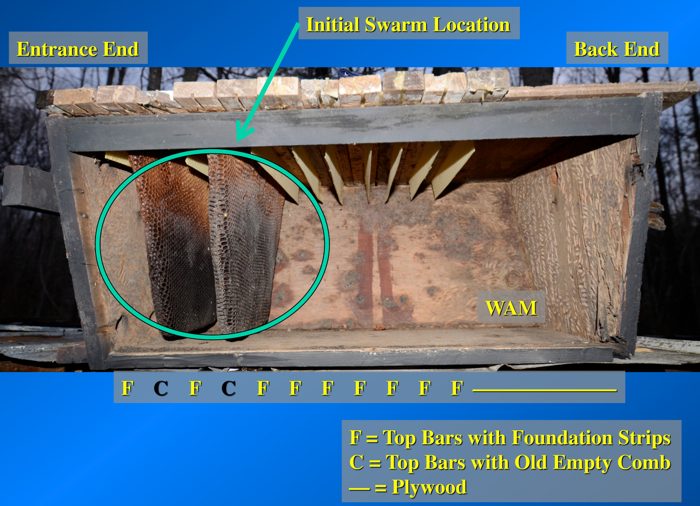

The next three pictures show how I arrange the combs and foundation strips inside a bait hive, using Hive 99, now a demonstration hive set up as a bait hive, first seen from a front corner. Two combs and the foundation strips are visible.

Below is Hive 99 shown from the side. The two combs are to the front (entrance end) of the hive with foundation strips between them. The swarm first clusters in the green circle. Then the colony grows to the back using the foundation strips to make new combs.

Below is Hive 99 looking up from the side showing the foundation strips. From this view, it’s clear they are the foundation of straight combs. When a strong swarm is in the hive, now it is worth committing more top bars with foundation strips (removing the plywood), and later transferring the colony to a longer hive. Notice ALL of the new combs are to my standard size, instead of luring the swarm to an odd-shaped bait hive and transferring the colony to a top-bar hive, destroying all the colony’s initial comb, a bad setback for the bees. Let the bees build your size combs from the first day they move into your bait hive.

Timing is Critical for Bait Hives

Early in the spring before my big rush and swarm season, I finish sorting the equipment for the bait hives; I put the empty brood combs in the hives, and set out the bait hives at numerous locations in about four counties. Getting the bait hives out early is a key part of my strategy. From a practical point of view, the bait hives are already on their locations well before the busy part of my spring season, which smooths out my workload and solves other logistical problems. For example, I do not want to be splitting nucs and putting out bait hives at the same time – not enough space in my pickup truck from moving all those hives without making extra trips, wasting daylight. From a biological perspective, sometimes swarming starts early. Occasionally a precocious swarm comes out extra early, maybe by a couple of weeks. In addition, bees start scouting for nest sites several days before the swarm leaves the hive, which adds to the general importance of setting out bait hives early.

After sorting the equipment for the bait hives, I load the hives on my bee truck for a trip to the out apiaries and other rural places (hunting survivor stock).

Mouse Protection for Bait Hives

Since the combs are not protected by bees, I always use a mouse guard, a wire grid over the entrances of the bait hive. Although the combs are empty, mice will sometimes chew them. Mice are excellent climbers, a feat not to be underestimated. My apiary game cameras (motion activated) record mice climbing trees at night. Very unexpected. If a mouse can go up a tree, then this climbing cousin of a squirrel can get in a bait hive placed high up, a well known strategy to make it more attractive to swarms. (See my top-bar hive book for details about mouse guards.)

Height For Bait Hives

While height gives the bait hive an advantage in being chosen by the scout bees, the combs inside are a powerful attractor even when the hive is lower to the ground. Because of speed, efficiency and safety, my rule is not to put bait hives any higher than I can stand on the tailgate of my pickup truck, about 6 feet, which is also a good height to make the hive attractive to the scout bees. That tailgate rule also requires I must back the truck up to the bait-hive site, which can be restrictive. Putting an empty and light bait hive up overhead is not too much trouble. When you put up a bait hive, try imaging how you will take it down full of bees and honey if left there too long (see below).

The two pictures below show typical bait hive locations, places with height but within tailgate reach, including sun and wind protection. The left picture shows a two-foot hive serving as a bait hive while in the right picture I am using a three-foot hive. As might be imagined from seeing the pictures below, make sure these bait hives are secure against spring winds (and a wind break is best).

Bait Hive Locations

For bait hives used to recover my lost swarms, I try to locate them a few hundred feet from the apiaries since swarms prefer to disperse from the parent colony. Other bait hives are far from known apiaries, intended to hunt survivor stock. Those surroundings are usually more unfamiliar. While rarely a problem, consider potential vandalism or inadvertently attracting bees, though temporarily, to places of human activity or to their pets or livestock. For example, I would not even consider putting a bait hive by (or near) an active horse barn (horses and bees don’t mix, an old beekeeping rule).

Painting bait hives to blend in helps them to be less noticeable. The scout bees can still find them mainly by odor. If not in a wind-sheltered place, which would be best, put weights on the hive. Hoping to “call” in the scout bees with old hive scent, I leave pieces of old comb pinched under the roof weights, right on the metal cover, to warm up in the sunlight, and to broadcast the smell of old comb in the air. Smash down the cells so they will not hold rainwater. (Save all scraps of old empty broken combs, even the pieces not worth putting in the solar melter since they still have the beehive smell. I do not use chemical lures.) Partial sunlight on the bait hive is acceptable, but a place that gets hot should be avoided. (See my top-bar hive book for other details on bait hive placement.)

Taking Down an Occupied Bait Hive

A bait hive can be quickly filled with honey by a big swarm. That makes it rock-pile heavy, awkward and strenuous to take down. Adding to the handling uncertainty, I typically retrieve bait hives at night. To make the work easier, the bee truck’s tailgate becomes a wide, stable working platform, much safer than a ladder, and I do not need to haul it. Of course the best method is to take down the occupied bait hive before it gets too heavy. Sometimes though, swarms move in for a while before I can retrieve them in a busy spring. Especially for sites away from my apiaries (trying to capture survivor swarms), I want to quickly replace the occupied bait hive with another. The hope is to catch an after swarm (if the first swarm was large like a prime swarm). Once I caught three swarms in about ten days at one site: a monster big prime swarm and two after swarms. The last after swarm was small, maybe a pound of bees (one-third of a package), not economically productive (except possibly for the queen stock). Still, I’m hunting that multiple catch.

End of Swarm Season: Retrieve All Bait Hives

The bait hives are only in the apiaries during swarm season. In my locations of Piedmont Virginia and due south in North Carolina, this time duration is mostly April and May during my local swarm season. At this time the weather is getting warmer (particularly the nighttime temperatures) and wax moths are becoming more active. Since the combs are empty, the rate of wax moth infestation is very slow and typically nonexistent. Expect less of a wax moth problem in bait combs north of Virginia and North Carolina and possibly more of a problem to the south. Also with the timing, know the local swarm season duration for your area, a fact well known to veteran beekeepers.

Spring 2013 has me “rolling out” my army of bait hives with even more hives. Make bait hives part of your beekeeping. It’s fun, full of surprises, and another way to enjoy beekeeping. For more information on bait hives and more photographs, see my top-bar hive beekeeping book available at the Welcome page. I hope you enjoyed looking over the pictures.

This bait hive top-bar hive page started out at about 3,000 words and 14 pictures. It takes a lot of time to accumulate the photographs and write these detailed pages. Please consider supporting this top-bar hive information with the donation button below. You do not need a Paypal account. Paypal just moves the funds and keeps everything secure. After clicking the Donate button, look to the lower left of the screen to the pictures of the little credit cards. Click the blue “continue” button, and places to put in credit card information will appear.

Thank you.

Kind regards,

Wyatt A. Mangum, PhD